Leading a team of individual contributors or technical specialists is not easy. Independent, proud and off-puttingly smart, experts intensely dislike being given orders.

But that doesn’t mean they don’t make mistakes that need to be corrected. Or that they refuse to be coached.

We use an approach called IGRROW, described below. Helpfully, it works as well virtually as in face to face conversation.

You can jump straight to the technique if you’d like. But first, it’s helpful to consider the question “what is coaching?”

(You may also be asking: “Are subject matter experts always difficult to work with? Do they need to be fixed?” The answer is no. We’ll cover that topic in an upcoming blogpost.)

What is coaching?

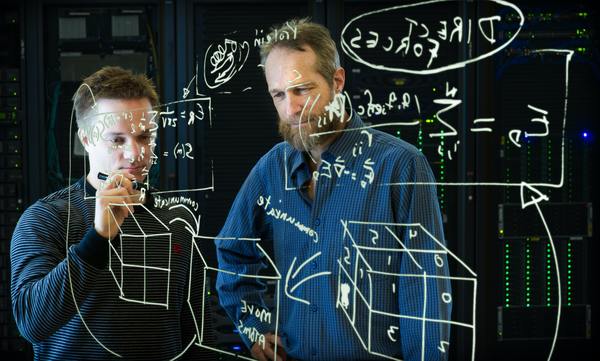

How can you coach very smart people to think through tricky organisational situations, and to commit to making positive change?

“Coaching” is a term used to describe quite a variety of different organisational conversations.

Most often it refers to an intervention, often uninvited, on the part of a manager to correct perceived problems with performance, behaviour or attitude.

That’s a legitimate action for managers to take. But does “reading the riot act” meaningfully change behaviour – particularly if the conversation is via a teleconference rather than face-to-face?

It’s rarely the best approach, particularly with experts. As a group who are used to working relatively autonomously, experts respond better to a two-way conversation than do to a lecture via Zoom.

Good coaching is a two way conversation.

We think of it as a process of inquiry by a colleague, a stakeholder, a leader or even a direct report. It aims to assist the “coachee” (the person being coached) to think an issue through and arrive at a course of action to which they feel committed.

That’s not necessarily formal. The conversation could conceivably be initiated by either party, and it’s not necessarily prompted by a specific problem.

A coaching conversation assists an individual to resolve a dilemma they face; to work through a complex issue, or to explore their future goals.

This approach also provides an effective way to intervene when an expert, from the coachee’s perspective, seems to lack self-awareness of their impact on others, or needs to change their attitude, performance or behaviour.

It is possible to coach experts who resist the idea of coaching, in real life or via teleconference.

But you have to take the right approach.

Coaching to change behaviour

Let’s start by considering a common need for expert coaching.

A leader has observed that an expert might need to adjust their conduct, or attitude or performance.

The expert as yet lacks the self-awareness to realise/appreciate that a change is needed. Or they realise change is needed, but they lack the skills needed to create change.

The reporting relationship between a manager and their report implicitly implies a “coaching contract”. It is the right and responsibility of the leader to raise the matter.

But while admonishing an expert has its uses, it’s less likely to build awareness and skills. A more Socratic approach is required.

Let’s imagine some or all of these behaviours have been observed: The expert arrives late for a meeting with a key stakeholder. They’re under-prepared, they build very little rapport, they interrupt or talks over the stakeholder. They don’t fully inquire about the stakeholder’s situation, needs, expectations, requirements and point of view.

Or the expert becomes obsessed with minor details, is stubborn, idealistic and opinionated, speaks in unintelligible technical jargon; is excessively wordy and complicates things, or behaves arrogantly.

Some companies tolerate this kind of behaviour, believing that “brilliance often comes at a price”. That’s a sub-optimal approach when the behaviour is so irritating to stakeholders.

In this situation, it would be irresponsible of a leader of experts to not raise such observations and seek to help the expert develop more effective relating behaviour.

Also, an expert rarely will have intentionally set out to treat others poorly. They are often mortified to hear their leader’s take on their interactions.

Using the IGRROW method

The most effective coaching we’ve found for experts is a conversational model called IGRROW, which carefully places and sequences questions to engineer a process of discovery.

It creates a constructive conversation that allows an expert to realise the potential shortcomings of their existing attitudes, mindsets, and relating behaviours.

Just as importantly, it helps the expert identify preferred alternatives, and to commit to a more effective course of action.

Intentions (I)

The leader – or coach, or any other person initiating the conversation – should begin by carefully considering their own INTENTION in initiating the conversation.

A helpful INTENTION is something like “I would like to help Frank develop increased self-awareness, and more useful ways of relating.” That creates a more constructive conversation than a vague INTENTION like “I need to stop Frank behaving like a propeller head.”

The conversation will feel different to Frank depending upon the INTENTION that drives it, in turn influencing his response.

Sometimes the coach might state their intentions at the outset of the meeting, so the coachee understands where they are coming from, but this is not always necessary.

Goal (G)

The coach then utilises GOAL questions such as “What would be the ideal relationship you’d like to have with the stakeholder?”

Or “What’s your measure of a really effective stakeholder conversation/meeting?”

Or “What would you like to have accomplished in that meeting just now?”

The coach should not impose his or her measure of success on the expert. Eliciting the expert’s view increases the likelihood of they will recognise gaps between their desired outcome and the current situation, and want to close the gap.

As we’ll see, in turn this helps the expert think through how their actions might close the gap. During the closing of the coaching conversation, they then commit to take appropriate action.

Reality (RR)

In the next stage, the coach moves the conversation on to explore REALITY – i.e. what actually transpired in the meeting? Was it in line with expert’s goals?

Our coaching framework asks for two “R”s – that of the coachee and the coach. Inquiring about the coachee’s perspective prior to asserting our own view, we’ve found, typically produces a far superior result.

The expert owns the gaps they identify, rather than merely being told that the coach sees a gap.

The coach can still make their own observations – but they should hold back until they understand the coachee’s view of the situation.

Helpful questions include:

“To what extent do you believe the meeting delivered the desired outcomes” – that is, what the coachee identified when asked the GOAL question?

“How did you feel the meeting went?”

“How do you think the stakeholder experienced the meeting?”

Such questions should hopefully elicit self-awareness and answers that match your concerns, thought that is never guaranteed.

Which is why the second “R” prompts the coach to express their take on reality: “Here’s what I observed: (you were late, underprepared, you seemed to irritate the stakeholder when you interrupted, spoke in jargon, were inflexible, and so on.)”

Options (O)

The coach then moves to OPTIONS:

“What could you do next time to get a better outcome?”

The intention is to draw out a comprehensive menu of possible action to take, from which the expert will select the actions to which they feel inspired to commit.

Ideally, the coachee will flesh out sufficient potential solutions – e.g. prioritise arriving on time and arriving prepared; not interrupting; not disagreeing so quickly but asking more questions of the stakeholder, and so on.

Nothing prevents the coach from also making suggestions, but a balance is important.

If the expert contributed two ideas and the coach adds another eighteen, the coachee will feel considerably less ownership of the way forward. Which in turn lessens commitment.

Will (W)

W stands for WILL.

Once the coach has a satisfactory list of possible actions to take, they then inquire of the coachee: “Which of these ideas are you committed to moving forward with? And when? And how?”

The session must conclude with the coachee committing to undertake appropriate action.

Effective IGRROW coaching for experts and subject matter experts: example questions

IGRROW is a great approach for smart people who instinctively reject hectoring about their behaviour, sometimes without even realising. It’s also well suited to remote workers and teleconferencing, where attention will wander if the coachee is not continually engaged.

If the coach is particularly skilled, the coachee may not even realise they’re being coached and think they’re having a natural conversation. If not, coaching is unlikely to be refused if the coach is explicit about the sorts of questions they’re asking and why.

That is, if the INTENTION is legitimate and compelling.

The IGRROW approach also work through questions like “What should I do about X?”, where the expert is wrestling with a decision and seek another’s input.

The process remains the same:

(I) “Do you mind if I ask you a few questions to help you think it through and decide what to do?” This implicitly says “I’m not going to tell you what to do or solve this conundrum for you.”

(G) “What would be an optimal outcome?”

(R) “What do you see as the primary issues or impediments?”

(O) “Let’s explore all of the conceivable options at this point.”

(W) “Which options appeal the most and why? Which do you believe might deliver the optimal outcomes?”

IGRROW conversations are also useful to explore outcomes that an expert wishes to move towards.

(I) “Let’s have a conversation about your career aspirations and see if we can shape a plan together.”

(G) “Where would you love to be with your career in the next (18 months?)”

(R) “How ready are you to take that next step (successfully)?”

(O) “What sorts of things could you start working on now so as to ready yourself? Let’s brainstorm together a list of possible actions.”

(W) “What order do you want to tackle these options in?”

Why coaching ?

As a manager, it’s your responsibility to nurture the effectiveness of experts. This coaching, and finding ways to help coachees accept coaching, one of the most important skills you’ll learn – especially as remote work becomes more a standard part of business.

Coaching helps you help experts answer their own questions.

Which is important as you aren’t likely to know the best resolution to the challenges they face, and you may not even know where to start with a query deep in a technical domain.

But you can still help. Coaching frameworks like IGRROW let you help determine a way forward even without knowing the answer yourself.